Blog posts

Number 1

(July 4 2021)

About 10 or 12 years

ago, I started work on a book that was meant to help beginning students to

overcome common difficulties they were apt to encounter when learning to

draw. For various reasons I never finished the book but, with a few updates,

I do think the information could be of value. In that spirit I plan to

post excerpts from the book while emending and enhancing some of the ideas

along the way, which will lead to slight disparities between posts. This

shouldn't interfere with understanding the main concepts

presented.

The initial text was

titled Drawing: A Quick Approach to Gaining Professional Level Skill. As

I continued teaching, learning and ruminating on the drawing process, it

occurred to me that a new way of ordering the information I was presenting

might give fresh insight. So, in that spirit (again), I retitled the

book: "Learning to Draw; Seeing and the Three Kinds of

Memory". This didn't require me to drastically change the

information I was presenting, only to reorder it in what I think, is a more

logical sequence. By posting This material on the Blog I am hopping not

only to offer new insights, but to illicit feedback about the overall concept

and the usefulness of the ideas.

I'll start by posting my

initial Introduction and then add subsequent chapters, in the coming

weeks. I will be adding visual examples, many from my classes but some

from other (I assume) copywrite free sources.

Introduction

Why another book about

drawing? It’s a legitimate question, since there are already

hundreds of worthy books on the subject. Yet, in my experience of 35 years as a

professional artist and teacher, I have encountered too many talented, even

gifted, drawers/sketchers/artists who have struggled on as draftsmen despite

having read these books and having taken countless courses, seminars and

workshops. There are some very good books out there, of course; I have read

many of them myself and have even used some of their advice in my drawing

classes over the years. But, these books generally take many things

about new students for granted. They assume that the readers have

already acquired basic ways of looking at the world around them, and that

drawing is a straightforward matter of transferring what they see to paper.

What is missing from

most of the books out there is an explanation of why the drawings you make

don’t look like the author’s examples. Some books do give advice on

how to overcome common problems that are encountered, but the advice merely

suggests approaches but doesn’t explain why doing these things is

essential. They give advice that is either incomplete or so

expansive as to lose focus on the main issues.

I wrote this book to

help demystify and explain the initial stages of the drawing process so your

drawings will look like the examples. Comprehending

the artist’s approach to seeing and organizing space is crucial to making rapid

progress as a draftsman. Once the drawing student has mastered the basic seeing skills,

other areas like learning style and development of hand skills, will improve

rapidly. As the student becomes convinced that he (or she) is on the right

track, he will become doubly committed to mastering technique and will then

begin to advance even more quickly.

Teaching students to see

has become a primary goal of my teaching. The students I work with must prepare

for careers in applied art fields by developing professional-level drawing

skills within two short years, often while carrying a full course load.

Although this book was inspired by my work with these students, the approaches

and methods I explain here are applicable to anyone.

No book can teach you

how to draw. Not even this one. What this book can do, however, is

give you a set of tips and instructions to follow (along with a little

inspiration) so that you can teach yourself. The actual learning process, its

progress, rapidity and extent depend upon your own will and

commitment. If you are among the fortunate few who were born with a

pencil grafted to their arm, then no prompting by a book or instructor is

needed. However, if you are like most of us, and you have some basic talent but

know that you need to work on it, then a book like this one is a good next

{first} step.

The first four chapters

of this manual deal with seeing, developing essential

memories, improving eye/hand skills, and an approach to learning so

that your speed of progress is maximized. This part of the book specifically

describes the “seeing issue” and shows you a proven set of strategies to

overcome the mental conflicts that cause so much frustration for

students. Once you’ve mastered the seeing correctly, you

will learn ways to speed up the acquisition of the other skills you’ll need.

The last few chapters offer information to help you with specific drawing

issues, like the rules of light and shading technique-- ideas to accelerate

your progress toward developing a personal style. Many of the thoughts on style

are my personal observations, and students are referred to other volumes, which

I have listed in Appendix B, to further expand their knowledge of the subject.

Seeing (part 1)

“Learning To Draw: Seeing and the Three Kinds of Memory”. It has become apparent to me during my years

of teaching, that by naming and examining each element that goes into improving

drawing skill, I could make the undertaking less mysterious and more logically

accessible.

In my view (no pun intended),

accurate Seeing must be understood before the various memory elements the

student needs to acquire can be absorbed most effectively. We must describe each of the three areas of

memory briefly, because, one of the three, in particular, directly affect

Seeing (artistic seeing).

The Three

Kinds of Memory

1. Memory knowledge of what things look like. I refer to this type of memory as a Mental construct.

2.

Technique. This is acquired knowledge and memorized

processes which enable the artist to enhance the believability and reality of a

drawn object or scene

Both of these types of memories reside in the Left-brain memory storage bank.

3. Muscle memory. This is the kind of physical memory you acquire by repeating a physical process over and over. Think doing a one and a half flip off the high board, tying your shoe or simply dashing off your signature.

4.

Seeing (artistically) goes way

beyond the optical component of looking at things. Of even greater importance is how the

brain processes that visual input. And,

it is the functioning of our memories (Mental Constructs), that is so crucial

to the Seeing process

Often,

even drawing something again (and again) doesn’t achieve the desired result. This is because something happens when, as

untrained artists, we try to draw something accurately. It is at this stage that many people, who

want to learn to draw, become discouraged, assuming that they do not possess the

requisite “talent”. But the problem is

not with drawing ability; it is with “seeing” ability. If you separate out the

act of “seeing correctly,” and learn and understand its several basic precepts,

then your development of drawing skills and abilities proceeds at a much faster

pace. A corollary is that those who

try to bypass the seeing step or don’t fully integrate it into their approach

improve at a much slower rate. I

have encountered many people who, having not absorbed this fairly simple

concept, have wasted years, changed the course of careers even, to hide or

compensate for that fact. Proportional

and angular measuring ability, for example, is one of the major processes that

form the basis for artistic seeing yet I have had students who felt measuring

(see Chapter 2) wasn’t “artistic.” that it seemed too mechanical or slowed them

down.; but nothing is further from the truth.

After a very short learning period, measuring becomes a natural even

instinctive aid to seeing which expands your artistic capabilities. We’ll cover

measuring, in more detail, later.

Seeing an object, the way an

accomplished artist would see it is a skill that most of us must learn, and it

is not so much an extended learning process as just changing your notion of how

to look at things. This can take as

little as five minutes (for the student who is already aware of the seeing

problem or 6 months for the student who can’t seem to pry himself loose from

old habits. Some students figure it out

on their own -- these are the advanced students in every class. Yet, for most of us, artistic seeing ability

is annoyingly elusive. To understand it

we must first talk about human brain function and how perfectly legitimate

habits we develop for one kind of activity can thwart or hinder or ability to

undertake a different sort of activity.

Psychological research into brain function has

created a whole new understanding of our thought process. Art educators and in particular,

Artist/writer Betty Edwards, in her book Drawing On The Right Side Of The

Brain, have made it common parlance to talk about the human brain and

thought process in terms of right-brain and left-brain. Memory, stepwise logic, math and language

skills, and digging an existing hole deeper (getting a PhD for example) are all

predominantly left-brain functions, while perceiving relationships and

spatiality, proportional measuring, and digging several other holes in

different locations (that is, exploring seemingly unrelated options) are

predominantly controlled by the right hemisphere.

How can we tell that there are distinctly different thought processes

which act in different but harmonious and integrated ways to help us navigate

through our days?

Two examples come to mind:

n When

you are driving, have you ever been so lost in thought (left brain function)

that you have driven for two or three miles before realizing that you weren’t

paying attention to what you were doing?

If you have had that experience, and survived, what was it that

prevented you from crashing into a tree or rear-ending the car in front of you? Answer: the right side of your brain, which

deals primarily with spatial relationships.

While you were on autopilot, daydreaming, your right brain was doing the

steering, adjusting your foot on the gas, and so on.

n Another

example is the venerable vase face optical illusion. Most people who have taken an art course have

run across this example; however, what’s really happening in the drawing of the

vase face isn’t always fully explained beyond the gee-whiz effect of its visual

ambiguity. But, it is an excellent tool for explaining the separation of brain

function.

In the exercise,

the student is asked to draw the silhouette of a face (Example - 1), and

then to draw an opposing silhouette facing the original. Horizontal lines are added to the top and

bottom to complete the vase illusion (Example 2). The crux of the exercise is that the first

silhouette is drawn from memory (left-brain), while the facing silhouette

requires the student to measure distances and try to match the shapes in

reverse while at the same time positioning it in opposition to the first

(right-brain). Try drawing a couple of

these and attempt to get a feel for the two different brain functions at

work. The two parts of the vase-face

drawing exercise rely on totally different brain processes; one memory, the

other spatial organization. Keep in mind how much easier it was to draw the one

from memory (utilizing your pre-existing mental construct for the

silhouette of a face). If you are still not totally convinced, I have

another example coming up that should help.

Having established that there are

two interdependent brain functions that, work in concert to govern our

day-to-day activities, let’s see what effect that knowledge has on our ability

to draw.

For the most part, our bifurcated,

or split brain works exceedingly well; after all, it has evolved over countless

centuries to allow us to cope with an increasingly complex world. In recent times, due to the emphasis placed

on left-brain functions by our modern educational system, the left side of our

brains gets much more attention than the right.

In our Western culture, as we get beyond second or third grade, right

side brain activities often take a backseat to left side ones in the public education

system. Thus, instead of emphasizing

subjects like drawing, music, and art we require math, foreign language,

writing, sciences and other subjects that rely heavily upon logic and

memorization. Because of this, most people,

as they enter adolescence lose or begin to ignore right-brain functions that

seem irrelevant to us when we contemplate the likelihood of a career tied to

our skill at using our left brain.

So, if we assume

the Left side of the brain tends to be dominant, why is this a problem?

A.

Memory takeover

As a child you probably did a lot

of drawing. Then, at about age 10 or 11, art (that is, drawing), took a back

seat as you began to concentrate on learning math, English, history and other left-brain

dominant subjects. If you even had an art teacher at that age, it would have

been unusual if he or she were into teaching fundamental drawing skills. Art classes you had would probably have been

of the more general all-purpose variety, with exercises in color, craft

projects, or perhaps computer graphics. Eventually, you either quit drawing all

together or if you wanted to persist, you started your own program of

self-study that, perhaps, involved copying comics, or some other pop culture

imagery.

You may possess only the technical

skills and knowledge of a ten-year-old or you may have been memorizing Anime

imagery or copying Lord of the Rings fantasy drawings, but it is important to

understand, that whatever skill level you have attained, the left side of your

brain, specifically, the part that keeps track of visual memory, will be part

of the mix when you attempt to draw a 3D subject from life. We rely on memory; it is, in fact, a large

part of why we improve in our ability to depict something. Each time we carefully draw a subject we

accumulate more visual data which then informs our next rendition of that

subject or other similar subjects

The difficulty arises when we or any

individual, at any skill level, relies too heavily on current memory to deal with a new subject. Someone who has not drawn since the age of

ten, trying to draw a real 3D house, will dredge up their “ten-year old’s

mental image” of a house (because it is easier!) with predictable results. A more advanced student, who learned to draw by

copying fantasy characters, will have a better idea for drawing the house

(they’re stored memory will be better) but they will still embellish with the

stylistic conventions of the memorized imagery.

The single biggest impediment to being able

to draw what you see accurately is the tendency of your left-brain (the dominant

half) to interfere with or take over the drawing function.

Left-brain takeover is what happens when a drawing you’ve

started, suddenly begins to go wrong.

Remember the vase face and how much easier it was to draw the profile

from memory than it was to draw the second, opposing profile? Your brain’s dominant half wants to take over

the function of drawing for the same reason: because it is easier. Whenever you draw something, your left brain

will try to impose its memory of that

object, no matter how imperfect that memory is. So, right in the middle of your drawing,

without realizing it, you allow your remembered concept of the object to take

over and distort the actual rendition you are attempting.

Object memories can be child-like

symbol memories that you developed early in life, (like a football with a

circle in the middle for an eye) but did not flesh-out because you weren’t

“into” art. Or they can be the more elaborate memories of the stylized work you

copied from during a later stage of your development. The result is that rather than drawing an

accurate rendition of what you are seeing, you draw an approximation of what

you see because you lack a tactic to help you draw it accurately, and it’s

easier just to revert to stored memory

You need an “approach” to drawing from

life that doesn’t rely on currently held memories.

Next we’ll look at strategies you

can learn that will allow you to resolve perception issues that create

distortions and that will help you build better memories (more accurate mental

Constructs).

Seeing (part 2)

In part 1 we learned how memory

takeover could cause us to distort a

drawing we were trying to make of an actual 3D scene. Next, let’s examine the way in which an

untrained person looks at the world so that we can better understand why it is

so easy for memory takeover to occur and how we can deal with it.

B. Regular old looking

The human eye has a cone of focus of only about 6 degrees. This means that when you fix your gaze on something, you can only focus your eyes on objects within a range of three degrees on either side of the centerline of your visual field ( a wedge whose horizontal diameter is only about a twentieth of your approximately 120-degree total field of vision). Within that range, there is a very limited depth of field for human eyesight.

So, using example_5 let’s suppose you are looking out of your window.

As you look past the praying mantis

on the drapes you notice a squirrel stealing seed from the bird feeder in your

yard, and just beyond the squirrel, still within your sightline, is the chimney

of the house across the street, and beyond that are the distant mountain

peaks. If you move your sight line of

vision, to focus your attention on the praying mantis (it looks like it’s going

to jump on your sleeve!) (See example 5A)

you will notice that all other elements in your six degree field (squirrel,

chimney, mountains) have gone out of focus.

As you refocus on each of these 4 elements in turn (examples 5 B, C

and D ) each of the other three go out of focus. If your line of vision drifts right or left (or

up or down), you will notice that each of the aforementioned objects goes out

of focus as you zero in on something else.

Notice also that objects within our cone of focus but separated

significantly in depth are also out of focus when we hone in on one object. Yet except for the times when we’re doing

exercises like this, we never notice how much of our world is out of focus at

any one time; Nineteen twentieths to be more precise. This is because we construct, in our mind’s

eye, an in-focus universe by letting our eyes continuously dart around,

focusing on everything of importance that we encounter. This is regular old looking.

One of the dominant left--side

brain functions I mentioned earlier was stepwise logical progression. For example as a math student you would

logically progress from simple arithmetic to geometry, trigonometry, algebra,

differential equations and then calculus and beyond. As a child learning to read you would start

by learning the alphabet then progress to simple word/object associations and from

there to simple sentences, grammar and so on.

The ability to understand logical progression is obviously a valuable one

for humans but it can be an impediment when it comes to rendering an object accurately

from life (when seen in three dimensions), especially when we use regular old

looking to do it.

An example of the problems inherent

in regular old looking is in order. Let

us suppose that you are going to draw a group of objects scattered about on a

tabletop. (See example-6.)

Because of your eye’s narrow cone

of focus, you will tend to focus on each object individually, and the left side

of your brain will want to process information from one object to the next in a

logical progression. The result will be

that you draw each object in turn moving from the Basket, to the wine bottle,

and then to the file box (or in some similar fashion). But soon you will be running into trouble,

because in your drawing, the objects don’t want to line up the same way they do

on the tabletop, and some even seem to be the wrong size when compared to one

another on your paper, the spacing is all wrong and, besides that, the

cylindrical objects and boxes look distorted.

This happens because when you see and draw the objects individually

(cone of focus; regular old looking), you’re not paying attention to how they relate

to one another with respect to either size or position. This is the most common issue with learning

to draw from life: loving details applied to improperly sized and incorrectly

located pieces of the whole, whether it’s a still life, a landscape or the

human figure.

What if there was a way to get

everything properly sized and in its correct relative position before

drawing the details?

The

“logical” approach of drawing objects one after another does not work because

when you focus on each object separately, without consideration for the objects

around it, you build in errors of both size and relative position. Don’t

get me wrong, there is a logical approach, it’s just not the one based on

focusing on individual objects and drawing them piecemeal.

The reason so many beginning

drawings have these distortions is again, because as you focus in, the dominant

left-brain wants to take over the drawing, imposing your currently held mental

construct in place of what you are actually seeing and, treating each

object or part as if it were separate!

In other words, the left brain

doesn’t perceive objects, in a way that is conducive to helping you draw, until

you teach it a new logical progression.

Relationships

You

can’t see the details of any of the objects, but what you can see is their

relationships to one another (see example 10).

Using this information you can then “block in” that is, you can locate and estimate

the correct size of all the objects

Then using very light pencil lines, you can just put down estimates

of where everything is going to be positioned in the scene.

So

At this point, you could, for

example, hold up your paper and compare your light, “blocked in” sketch with

the actual scene---that’s why they invented the easel. Squint if you must, to soften the focus of the

three-dimensional scene so you can make the comparison. (see Example 11). The method of seeing everything as a first step is the reason that

experienced artists always seem to have all of the objects in their scenes in

the correct positions with the relative sizes correct. Once you have established the positions and

sizes of the objects, then proceed

to work on the individual parts just like the pros do.

A little practice seeing the three D space

flat and blocking in basic shapes will almost immediately begin to improve your

drawings.

So, adding the narrow cone of focus

stuff to step wise progression gives us “Regular old looking”, which along with

“Memory takeover” make up the two main impediments to seeing correctly. In the next installment we will look at the

ways to prevent or override the Left-brain tendency to interrupt and distort

our attempts at accurately depicting what we see.

In Seeing 1 and 2 we discovered that the way our brain is

wired can cause problems when we attempt to draw what we see accurately, and that

being able to see accurately is essential to improving our drawing skills

quickly. Below I have listed several

interrelated concepts that you can master in a very short time. Once these simple ideas are understood, the

perceptual difficulty of seeing can easily be overcome. I’ll list

them first and then we’ll take a closer look at each one.

Measuring relationships (three

kinds of measuring)

Measuring proportions, angles and vertical/horizontal relationships.

Treating Objects and Spaces Equally

Artists see the spaces between things

as well as the things themselves because on a flat surface both have equal

weight. You’ve heard the term “negative space”

referring to the space around objects. I

like to think of it in terms of “gaps,” or the spaces between objects

Seeing Flat

Seeing flat is the ability to see the relative sizes and spatial relationships

between multiple objects simultaneously. This ability comes from learning to

treat objects and the gaps between objects equally. Once mastered, it will be like having a

photograph of any scene you wish to draw, and thus the sizing and spacing of

the elements can be easily established.

This is the primary skill needed for seeing as an artist.

Other Kinds of Relationships

Once you begin to visually flatten

space, other kinds of relationships become apparent.

Lose Control Early to Gain Control Later

If you are very loose and light with the pencil to

begin with (blocking in with no details), it will pay big dividends with your

final drawing. This leads to a discussion of “touch.”

Avoiding Names for Objects

If we go with our instinct and think of what we are seeing by its object name (i.e. thigh, tree root, vase, etc.), our left brain will try to superimpose its stored symbol memory for the actual object. If we think of the thing we are seeing as a simplified geometric form rather than a named object, it is easier for our right brain to guide the drawing function, and we will get a more accurate drawing.

Measuring

I usually start a first class by explaining the separation

between the right and left brain and left-brain dominance, followed by an

exercise in which I have students draw a “vase face” to demonstrate how the

separation of brain function works [Seeing (part 1)]. Then, I put a plain cardboard box on the model

stand and tell students to make a line drawing of the box. Everyone can draw a box, right?

Most of the drawings look like some version of Example #12. (if they know a bit about Linear Perspective)

The student sees this (Example 13).

But, their previously held mental construct, causes them to make a drawing something like Example #12!

This happens because the typical, untrained student sees the

box in front of them and then unconsciously allows his left brain to

superimpose his previous memory of “a box” onto the drawing he is trying to

make. This causes the distortion.

The drawing becomes an interpretation of the student’s left-brain

“A Box” memory with its suggestion of dimensions even though the

student’s view of the actual box and its measurable dimensions

are quite different! In a left-brain

sense, this interpretation is a sound approach; the left brain carries logical,

manageable, simplified memories for everything—although most are not

specific. So, if the left brain takes

over, its interpretation of the object will show a logical understanding of its

properties, but not necessarily what it actually looks like in its current

position.

We will now look at the measuring process

Measuring Relationships

Measure Proportional Length/Width/Height

Let’s look at what has just happened and demonstrate something called “proportional and angular measuring.” We’ve all seen the picture of the “artist” (usually wearing a beret and sporting a pointy little mustache) holding his pencil at arm’s length and “artfully” sighting the subject of his drawing. What he’s doing is comparing the size of two objects in his line of sight; or, comparing the width of an object to its height; or, comparing the height or width of an object to the space between it and an adjacent object. Like this archetypal sketcher, you too can compare anything to anything using this method—and the beret and mustache are optional. Look at Example #15.

Notice that the artist is sighting between the top of the

pencil and his thumb where he’s grasped the pencil. Although many teachers suggest that you do

this with your arm fully extended, it’s not required. As long as the pencil

stays at the same distance from your eye when making the comparisons (between

two objects or object dimensions, etc.) the proportional relationship will be

correct. So, for example, you might

determine an object’s height is a little over twice its width or that the

object’s width is about a third the size of the gap between it and the next

object. This process of measuring sizes

and relationships is something your right brain does a lot better than your

left brain and by doing it, you’ll be ensuring that you are drawing the objects

in front of you and not substituting a left-brain mental construct. At first, for many students, this approach

seems not “artistic,” when in fact, learning to measure objects and distances

for yourself becomes routine, lets you see more quickly and clearly—and, in the

long run, increases your confidence as an artist and your ability to interpret

more “artistically.”

Measuring is probably the most

important and effective method you can use to prevent left-brain memory

takeover.

In the box example (Example #13), if

the student had made some simple measurements for locations of vertical corners

and related all the measurements to the height of the nearest vertical, then

the drawing would look more like Example 14.

Measure angles

You can also use the handheld pencil

to measure angles. Sight

align it with the angle you wish to duplicate, hold your drawing up and then

simply scribe the angle on your page while making a visual comparison with the

original angle you sighted (in the case of example 16, the roofline across the

street.)

When doing this kind of measuring

you should ensure that you keep your pencil vertical (perpendicular to your

line of sight) as there is a tendency to point your pencil in the direction of

a receding line you are trying to get the angle of. Just remember that the angles you measure

must be translated to a flat surface so your initial measurement should be made

with this in mind. Deborah Rockman in her book The Art of Teaching Drawing instructs

students to think of the pencil as a clock hand and estimate the time (3 o’clock

the small hand being horizontal.) You are translating three-dimensional

information to a two-dimensional surface and this is why you need the imaginary

flat surface, like a clock face, to reinforce the necessity that your pencil

remain perpendicular to your sight line during the angle measuring process, to ensure

an accurate translation of the 3D visual data to your 2D drawing surface.

Vertical and Horizontal relationships

A third use of the pencil for measuring is in sighting

vertical and horizontal relationships.

This is an aid to seeing relationships in a complex form (the human

figure) or group of objects, and helps us to position them correctly. (Examples

#19, 19a, 19b.)

Measuring By measuring angles,

proportions and vertical/horizontal relationships you avoid making errors caused by the tendency

to rely on faulty mental constructs. At

the same time, you are transferring an accurate, flattened view of 3-D

information onto a 2-D sheet of paper.

When students do the “draw the box”

exercise, it is amazing how many cannot see the correct version of the box

until they use the measuring technique to actually compare the dimensions –

by measuring, they are disproving their incorrect mental assumptions!

Objects

and spaces are of equal importance

Let’s revisit the bottle, the basket, and the box. (See

example #6)

In this example,

notice that there is a gap between the bottle and the basket and between the

bottle and the box. This gap is called

a negative space. As we have seen, the left-brain

cares about focusing on objects and lining them up in a logical progression. But it doesn’t care at all about empty

spaces. So, try this: draw the shape of

the space between the bottle and the

bowl. When you do this, you are seeing

both of the surrounding objects simultaneously and to do that are using the

right side of your brain. Because your

left brain has no ready-made symbolic memory available for a negative space,

and therefore cannot impose an image on your drawing. As a result, your rendering should be very

true to the actual shape and dimension of the space in between objects which

happens to be shaped exactly like the edges of the objects themselves.

Another way to understand this is by thinking about the “Gap” or space between two objects.

The only way you can perceive the size or shape of a space between two objects is by staring in the direction of the objects and not focusing on either object but rather allowing your peripheral vision to gage the distance between them! You didn’t focus on either object but allowed your mind to flatten the space enabling you to see the gap accurately. With a little practice it becomes easy for you to flip the mental switch, stare in a direction, out of focus and determine the correct relationships between multiple objects or elements of a scene and thus letting you

Seeing

Flat

When I use this term, I am referring to the acquired

ability to look at a three-dimensional scene and see its various components as

if they were on a flat surface (as though you were looking at a photographic

print of the scene). You will recall

that we have a very small cone of focus and that our visual depth of field is

very limited, so the untrained eye tends to focus on individual parts of a

scene (first the praying mantis, then the rooftop, then the mountains, and so on).

The artist’s eye can do that too, but the artist’s eye is also able to

look in the general direction of this group of objects (without focusing on any

single element) and see all three simultaneously! Of course, they will not all be in focus, in

fact, none of them will be in focus, (remember Example 10-11), but

in this case, they don’t need to be in focus because what the artist wants (at

least initially) is not a sharp image of any one object, but rather the size

and placement relationships among all the objects.

By looking at all the objects

simultaneously (focusing on none), the artist can see how far apart they are

(the Gaps) as well as the various linear and shape relationships that would

never be apparent by looking at the objects in focus and one at a time! This is why artists can draw a group of

objects in a still life and get them all the right size and in the correct

place.

And finally, remember the example of the roof line angle and

drawing pad? Take a look at example 16-17)

If you tried that and compared the roofline angle with the one you scribed on

the paper, then you were “seeing flat.”

The pad is three feet away, and the roofline is forty yards away. To be able to see them both simultaneously,

you had to look in the general direction, but not focus on either. In fact, if you compared the angle of your

drawn line with the angle of the mountainside you are comparing two things that

are forty miles apart (in depth)! Seeing

out of focus allows you to do this. The

dominant left-brain wants to focus on individual objects and proceed logically

from one to the next to the next . . . and in doing so prevents the right side

of your brain from seeing the “relationships” between things.

We’ll complete the list of Artistic Seeing aides in the next

installment.

Exercises

1. Draw some vase faces. Refer to the Examples 1 and 2 as you do it but imagine your own unique profile.

Draw the first part from memory, and then draw the second, facing

part. Think about the different process your

brain uses to draw each version of the facial silhouette.

2. Draw some gaps. Look at the shape of the space between two

buildings or objects and make a line drawing just of the gap or space between

them. In perceiving the gap you are

requiring yourself to see more than one object even while you’re seeing a

relationship between objects! A

relationship you might never have noticed before. Some call this negative space, which it is,

but I think the term “gap” helps you understand the concept on a more basic

level.

3.

Practice

proportional and angular measuring. To

get used to the idea, set up a chair in your room facing objects on the other

side. How wide is the bookcase when

compared to its height? The same? Three

quarters of the height? How far is the

wall clock from the window? Two times

the width (diameter) of the clock? And

so on . . . If you have trouble with the

pencil sighting just pinch the distance between your thumb and forefinger to

make the comparisons. With a bit of

practice this becomes a part of your approach to drawing a scene or objects.

Seeing (part 4)

Measuring, flattening space, and controlling left-brain

memories are essential skills, but several additional concepts can greatly

enhance your seeing capabilities.

Other

Kinds of Relationships

Once you have developed some skill

at seeing flat, other comparisons beyond simple spatial and size relationships

become possible. Parallel relationships

and lines that flow into other lines are examples.

It takes only a little

practice to develop the skill of seeing parallel relationships or lines that

extend into other lines once you understand the trick of perceiving gaps. Try this: Look for parallel lines that

stretch the limits of your perception. Take

Example 20. You could use the angle of the

student’s upper arm resting on the table. It happens to be parallel to the receding edge

of the desk beside him. And that, in

turn, is “lined up” with the lower edge of the box surrounding the shapes on

the dry erase board.

To help you understand

this you can make your own “relational” seeing exercises. Try looking for parallel curves or other

shapes that are similar to each other. (Look at Example 19 again and then look

at examples 20.5 and 20.6.)

So, you can begin to understand that flattening space

(mentally) not only helps us improve the accuracy of our pictures, it also

opens up other, more advanced ideas about the way in which we construct

them.

The possibilities are limitless. This ability to notice and apply a subtext of

consciously perceived relationships, which anyone can acquire with a little

practice and imagination, lies at the heart of compositional structure that one

discovers in the drawings and paintings of the Masters. See Examples 21, 22,

and 23.

By looking at a group of objects without focusing on any one object within

the group you can perceive relationships between objects, distances between

objects, size comparisons of objects, parallel relationships, and other spatial

information that is not available to you if you only let your left-brain take

over and focus on individual objects.

Lose

control early to gain control later

In my work with students, I have come to realize that in many

cases the problem of getting lost in the details of objects could be alleviated

by simply changing the way the pencil is held during the initial stages (the blocking-in

stages) of the drawing. Normally, whenever

you find yourself gripping a writing instrument (Example #30), you’re getting

ready to engage in some detail-oriented process like writing down a phone

number or doing a math problem. So, your mind is trained to start focusing from

the instant you pick up the pencil.

By gripping the pencil in a way that prevents you from

drawing details, you have immediately taken away the ability to be in control—which

can be scary. When I encourage students

to use a more relaxed grip as in Example 31, they are often uncomfortable at

first. They feel the loss of control. But, losing control is exactly what you should

do at the blocking-in stage of a

drawing. You are only interested in very

loosely and lightly sketching out the size and location relationships of the

objects anyway! So, holding the pencil loosely

will keep you out of the left-brain detail mode, and help you concentrate on

getting the relationships in the

drawing correct.

Example #30 Control position; working on

details

Example #31 Allow the pencil to float—holding it loosely

with thumb, index and middle fingers (not touching

the fleshy web between index finger and thumb).

This prevents you from focusing on details, which inevitably happens if

you are holding the pencil like an accountant (control mode, Example #30).

Remember, you only want to be setting up the image

by drawing “blob” shapes very lightly but in the correct spatial and size

relationships to the other “blob” designated objects. So, no details. Everything drawn very lightly. The advantage of this technique—blocking-in

marks drawn faintly—allows you to add the finishing details later

without having to erase.

Use the same process on any subject. Notice the torso of the nude is treated as a parallelogram. You can simplify the thigh jutting forward as

a plexiglass cylinder, correctly sized and placed to which you then add

details. See the next section.

Avoiding

names for objects

In this process of translating 3-D information into a 2-D representation of that information, the more you can objectify the things you are trying to depict, the more successful you will be. “Objectification,” in this context, is to see the object as a simple geometric shape. The blocking-in process uses this notion.

Look at the above example to see a problem that commonly

comes up for students when they are drawing from live models. A student, when confronted with a

foreshortened view of a portion of the body—the thigh for example—may have a

great deal of trouble trying to draw it correctly as seen. Here again, that old left-brain dominance is

the likely culprit. What may be happening is that the student’s left-brain has

a mental picture of a thigh which it tries to impose on the drawing. Since that mental picture has little to do

with the actual scene the student is observing, the result is usually a very

distorted or bent-down (differently angled) version of the thigh that has no

resemblance to the actual image. In

cases like this, I suggest the student try to visualize the thigh not as a

thigh but rather as a transparent section of Plexiglas pipe. (Plexiglas pipe is a good substitute in this

case. Since it’s a visually neutral

object, the student probably won’t have an existing mental picture of it.) On seeing a piece of pipe, the student only

needs to approximate the overlap between the openings at either end, and

then refine the thigh shape-contours to that construct. See Diagram F-1 and the "This, Not This" diagram

that follows.

The resulting drawing is close to the observed configuration

because the left-brain “thigh” memory wasn’t required to create it.

Converting familiar but difficult-to-draw objects into

simplified forms, takes away their name/memory relationship and makes them much easier

to draw correctly. This is closely

related to the concept of blocking in.

The main difference in this example is the addition of a 3-D component

that comes into play when the student visualizes both ends of the transparent

cylinder. Most blocking in needs only

flattened shapes to represent elements in the composition so that their

relative placement and size are initially established.

Summary

I cannot stress enough the need to be able to see correctly. If you bypass this step, it might derail all

your subsequent efforts at improving.

The next step for you as a student is to practice these

techniques for a week or two to ensure that you have mastered them and can use

them in your future drawing. To recap,

here’s what you should be working on:

·

Measuring

techniques: Sight with your pencil to

make relative size comparisons and to measure angles for translation to a flat

drawing surface

- Seeing flat, understand and use

gaps: Consciously visualize spaces

between objects—get used to the idea that spaces and objects are coequal

- Looking for relationships

between things: revisit Seeing (part two) “Relationships”

- Control the tendency for the

left side memories of things from taking over in the middle of a

drawing. Embrace “measuring” to

help you to avoid overreliance on existing memories

You have now reached an important plateau. You can correctly

draw what you see. This doesn’t mean

that every drawing will come out as you want it, but with your newly acquired

skills you will be able to identify and correct problems of spacing and

relative size in your drawings. Over

time, as you continue to draw, the number of corrections you have to make will

be fewer.

Once you understand the process of “artistic

seeing” you will be able to correct your own drawings and the progress you make

developing your skill should be much more rapid.

Next, the three kinds of memory.

Three Kinds

of Memory (part 1)

There are three kinds of memory you must develop to evolve as

an artist. Two of these are closely

interrelated and we will discuss them in this Section. The third area will be covered under the

broad umbrella of Technique in the next section. .

1.

1. Mental Constructs of things --A constant

upgrading of your understanding of what things look like; not just the surface

detail but the structural identity as well.

2. 2. Muscle memory—the constant translation of visual data, through the hand to the page, that, over time, trains the hand to better, more concise and descriptive marks.

Mental Constructs and Muscle Memory (are interconnected)

We just spent a whole section devising ways to keep our

memory from distorting our drawings, but that doesn’t mean that memory doesn’t

play a part in the drawing process.

Before we can properly understand the essential role of memory in

drawing realistically, we need, to understand how currently held memories, if

not regulated, can take over the drawing process. The act of drawing is a balancing act between

what you are seeing and what you have stored in your memory about the subject

of your drawing. When you begin to learn

to draw, you don’t have very good memories of what things look like and rely

mostly on symbolic or generic conceptualizations of those things, and if you

couple that with the tendency of the left side of your brain to take over the

drawing task (remember _Ch 2_), your results will most likely end up as a version of reality that

has been influenced by your imperfect symbol memories and thus does not look much like

the scene. It is at this initial stage

of the learning process that your capacity to see correctly will pay big

dividends because it is at this stage--when you do not have a very good handle

on your subjects--that you must try to expend extra effort to be accurate, that

is you must use the techniques of Chapter 2 to insure you are being accurate

and not succumbing to the tendency to allow the left brain to substitute

symbolic information for what is really in front of you. When you take this extra care you improve

upon your existing memory of that scene, and this upgraded or improved memory

will, in turn, improve any subsequent drawings you may make.

If you always make a

conscious effort to strive for accuracy when you draw, the knowledge that you

gain in the form of better mental constructs will help you to make an even

better drawing of any new subject.

These better

memories of things (everything!) come from drawing, lots and lots of drawing

and concentrating on accuracy. Let me

make an important distinction here. The

drawings that you make of things (especially things you are unfamiliar with)

are really to analyze those things, and this analysis only works effectively if

you have learned to “see” correctly and actually do a carefully accurate drawing of the

object in question. I’m not talking here

about an hour and a half of shaded and embellished rendering – although you can

do that if you wish - I just mean about five or ten minutes of solid structural

analysis in which you look at major (prominent?) details of form and include

them in the overall sketch. This careful

analysis is what builds substance into your memories of the stuff around

you. If a student doesn’t realize the

importance of taking this extra care, no matter how zealous his or her efforts,

a lot of the time will be wasted. Slow

down, and build your artistic abilities on a solid foundation of knowledge

especially if you are an “applied arts” artist who really needs to be able to

utilize and manipulate real world visual data.

Drawing

and Sketching

As a beginning artist you should be drawing all of the time,

drawing everything, utilizing your newly acquired visual skills to analyze the

world around you. When you are drawing

and sketching, you are usually on location and working at a moderate size, say between,

6 x8” and 11 x 14”. If you are in the beginning stages of learning to draw, I

recommend that you use pencils of medium grade (F, HB, B – primarily because

they hold a point longer, and are more forgiving for the artist who has not yet

developed control over pencil pressure [touch]). You should also carry an eraser. (Note: a good, economical and practical solution is using the Standard HB Ticonderoga brand pencil with an attached eraser) When you are drawing, you should not let

mistakes you notice when comparing your drawing to the scene you are working

from, pass; fix them, because you are

trying to train the right side of your brain to function properly, that is, to

add to and improve the visual data you have already stored, and, by allowing

mistakes to go uncorrected you diminish the effectiveness of that process.

Some

Practical tips: most

drawing books suggest that you do a simplified drawing of the object you are

going to sketch and then add the details.

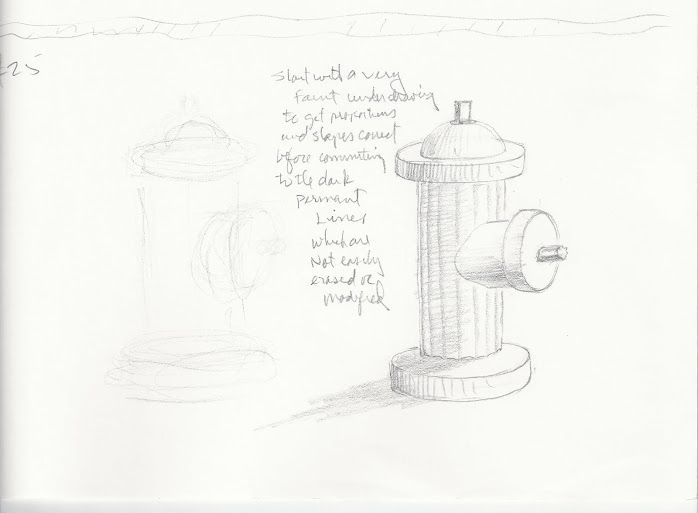

So, to draw a fire hydrant for example, you would start with a vertical

cylinder, and so on…. This is a valid

suggestion as far as it goes but, what never was made clear to me (and which

took some time to realize) was that that first cylinder should be drawn very,

very lightly and loosely so that you can

visually compare your drawing to

the object to check that you have the overall proportions correct (see example 25

This will allow you to make adjustments to your drawing (also very lightly) before proceeding to the

bolder, finish lines. In the case of multiple objects (as is most often the case!) using this very light approach allows you to check relationships in size and position before proceeding to finish . (See Example #11 under "Relationships"). This way, you

haven’t committed to a bunch of dark, unfixable lines that are in error. Using especially soft pencils for this work

is also not advised since they are crumbly, messy and become dull very

quickly. Mistakes when erased tend to

smear, adding to the mess. Until your

hand skills and touch have improved, I advise you to use a selection of several

mid-grade pencils (B, HB, F) with 2 or 3

of each grade, all sharpened, to improve results.

Everything you draw with careful observation will become a

memory that will aid in subsequent efforts-- not only in subsequent live

drawings of other things, but in building your capacity to draw things from

memory. Let's call it increasing your "Imaginative Range".

Sketchbooks

and Visual Diaries

You should keep a Personal Visual Diary if you are serious

about becoming a visual artist of any consequence. It should be a personal record of your

artistic journey. It can contain your

thoughts, ideas, things you want never to forget, drawings, descriptions of

techniques, coffee cup stains, a visual record of the places you have been and

the ideas you have considered. In short,

it should be a reference book about you and for you. Even if you do not plan on becoming a pro, a

sketch/diary will still be important, not only as a reference to previous

insights but as an historical record of your artistic journey.

Sketch book diaries should probably be hard bound books or

the newer hard bound book with a spiral binder which lies flat for drawing and

should be regarded as an important personal document and treated that way.

Copying

and Close Scrutiny: Why and how to copy and

how it worked for me

“The masters must be

copied over and over again and it is only after proving yourself a good copyist

that you should reasonably be permitted to draw a radish from nature”.

Degas

Once you are convinced that having better (more accurate)

memories of the way things look will help you to draw them better, the next

step is the building up your store of memorized information. If, for example, we wish to become more

skillful at depicting the human form we can copy great drawings from the past,

not only to train our eye-hand skills but to increase our knowledge. Later, when we work from the live model we

can utilize knowledge and conventions we have acquired from close observational study (copying)

to help us produce better results. This

does not happen all at once, so we must be persistent, and approach each “copy”

as a valuable learning experience.

Analyzing and deconstructing the work of a great artist, if approached

properly, can be like “channeling” their

knowledge (a Master Class, if you will) from the distant past. At the

end of this chapter there are several copying exercises with a detailed

description of the approach to use.

The best way

to copy

Assuming we want to develop our knowledge (mental constructs)

of things, then it makes sense to copy versions of those things we want to know

more about. There are three main ways we

could undertake this process.

1. We could set up the object (s) on our desk and

draw from life, or

2. We could take a picture of the

object (s), print it out, and then use that “flattened’ version to do

our drawing. This would simplify our

task as it would make space and size relationships more readily apparent. Lumped into this flattened out versions

category would be magazine pictures, paintings, comic book illustrations, and

so on; just about anything we can get some sort of picture of. But, let’s say we want to maximize the amount

of knowledge we get from a copy. How about…

3. Copying a competent existing drawing of the object or objects we wish to develop knowledge of. Not only can you learn shape proportion and detail but also the kind of marks used (technique) to develop the drawing, (obviously when using this approach you are limited to the view of the object determined by the artist whose work you are copying).

There is no correct answer to “the best way to copy”. It, of course, depends on the draughtsman’s knowledge and skill level. But for beginning and intermediate level artists who are intent on improving their skills and knowledge, then I recommend copying existing work in the same or a similar medium.

I have a term I use called Close Scrutiny which I define as

the careful copying of works that are pertinent to your area of interest. Most serious books on developing drawing

skills advocate copying. It is not

enough to simply look longingly at work we admire. We must “get into it.” If you force yourself to struggle to

approximate the sorts of marks that are embodied in highly skilled work you

will, inevitably, absorb portions of that dearly acquired knowledge. I feel the

best way you can do this by trying to reproduce it in your own hand. If you wish to learn to play the guitar you

wouldn’t just study chord diagrams in a manual; you would actually try to

imitate and test these diagrams by working with the instrument, over, and over,

and over again. And if the first few

times you couldn’t get the fingering correct, you would persist until your

fingers and hands, “did what you wanted them to.” You could probably learn to play the guitar

without the manual and study of previous music, but it would be a much longer

process, and if you tried to learn the guitar without practicing fingering, you

would fail. In a like manner, you must

train your hands and enhance your memories if you wish to improve

drawing abilities.

When I was a student, in my rendering classes and mechanical drawing I was fine and did well because I could focus in (remember the 6 degree cone of focus?), but in the figure drawing classes there was that annoying 3D space and all that unfamiliar complex detail that I had no memorized conventions for, to contend with; I was lost. My drawings were never finished and the parts that were, always seemed distorted and incorrectly positioned. My first semester instructor was sympathetic but not that helpful, and I remember his rather unspecific suggestions that I “be looser” “draw faster” and “let it flow,” I was particularly distressed when he suggested I just “draw loose like Rembrandt,”. He didn’t know how to tell me what my problems were and although I improved, mainly because I was looking at other student’s drawings, my progress was frustratingly slow. ( Note: I realize now that this disconnect I was experiencing was due to my lack of understanding that I had to set up "relationships" before working on details See section on Relationships )

The next semester I started in the same funk though my new

instructor was more helpful with his suggestions “Look at negative spaces” (if

he had used the term gaps [under "Seeing" see "Objects and spaces are of equal importance"], I would

have caught on a lot faster), “Get your proportions correct” and “look for the

gesture”. Beyond that, my hand was

beginning to make better marks. He

suggested that I make some copies of some Master drawings and start looking at

anatomy (At the time there was no specific course in human anatomy). Well, I was so balled up in my classroom

inadequacies and with other courses that I didn’t pay much attention at the

time. But I determined that I would

stay in Providence that second summer and really work on my drawing. I recalled his suggestion that I copy some

Master drawings, and I asked him what artists he suggested. He said, “Pontormo

as a good place to start”, he also added

that starting to build a personal art library and getting an anatomy book would

be a good idea.

I found an old copy of an anatomy book by Jeno Barcsey in a

used bookstore. The models in the book

were strange looking, but the pencil renderings were spectacular. I wanted to be able to draw like that! Not knowing where else to start, I began to

copy the illustrations in the anatomy book; at first the individual bones and

later the muscles and muscle groups - copying them to learn about the shapes

but also to learn his rendering style. It

was one of those epiphanies I mentioned in the introduction when I realized

that if I used my rendering capabilities to copy drawings I admired that I

could really learn technique and anatomy at the same time! So I’m copying anatomy and I’m copying master

drawings and I’m attending the open summer session figure drawing classes, and

no one is telling me to draw faster or like Rembrandt! And this led to a couple of other

discoveries. First of all, that the way

anatomical details in the Master drawings were drawn, were conventions for drawing those same body parts when I got to the

live figure sessions. Now It Was

Beginning To Make Sense! Second,

this stuff I was making copies of was beginning to be embedded in my memory – I

was replacing my earlier inadequate memories with much more serviceable ones. To be sure, when I drew, these memories could

dominate if I let them, but by regulating or balancing the use of the good

memories with honest right-brain analysis of the current subject, I was on my

way to competency. It was only years

later, when I began teaching drawing myself, that I realized the richness of

content one could acquire in just one copy, if it were undertaken with the

correct approach.

In one seriously undertaken copy of a master drawing a student would be:

·

learning anatomy along with

·

conventions for anatomical parts (a knee from the front for example),

or a method for suggesting foliage.

·

The

Masters shading technique and edge handling and line quality. Copying these

subtleties of drawing are invaluable to building your own muscle memory and

understanding of technique.

·

The

nuance of the Masters compositional

structure, See the El Greco, Example .#80

·

While

improving the ability to use right side

measuring technique and seeing of relationships; You are comparing copy and

original side by side, and mistakes are easier to pick out than trying to

compare a drawing to a live, 3D situation.

·

Developing

the habit of accuracy; of recognizing and correcting mistakes –

The drawing doesn’t get up and move after twenty minutes plus the space is

conveniently flat all at the same time!

I should note here that the struggles I recount are primarily with the human figure and anatomy, but are equally applicable to any genre whether it be landscape, still life or any other form when drawing from life or copying.

So, as you can see, improving Mental Constructs and training

your hand to make better marks inevitably incorporates the development of Technique,

which we will cover in more detail next.

The Third kind of Memory Technique

So what is technique

and how do I get some?

Technique, as I define it is the accumulation and/or

evolution of knowledge that increases the artists illusionistic skills and

that, when coupled with physical adroitness, become manifest in an artist’s

work.

When you attempt to draw a picture of something you see, you

are creating a two dimensional illusion of

the subject. Learning how to create this

illusion is basically the learning of technique. A common misconception is that you can bypass

the learning to “see correctly” phase of learning if you have good

techniques. Nothing could be further

from the truth, and the lovingly rendered but grossly distorted images made by

earnest amateurs are testament to this fallacy.

Being able to “see” so that you can get the shapes and relationships in a scene to be correct (accurate) is the necessary foundation of a drawing but it is only that, the foundation. For the drawing to have life, you must learn technical skills. Just as a magician (illusionist) has a bag of tricks, the artist’s techniques are the tricks that create the illusion on the page. The more technique the artist learns, the greater the impact of the illusions he/she can create. This knowledge of technique resides in the memory bank along with all of those “better memories” artists pick up as they draw from life and make copies and as they repeat these techniques over and over again their hands are becoming more adept. Remember the drawings in the Barcsey anatomy book that I really liked, and remember that I realized I was learning Anatomy and technique when I copied them? This is the basis for my contention that an artist can make the most rapid progress learning to draw, the figure in particular, when they copy from the best (the Masters) in the same or a similar medium (see Section on copying, page x), because they are multi-tasking. A finished drawing can take many forms, from a quick gestural sketch to a highly finished, almost photographic, rendering which might take days or weeks to complete and in between there are countless intermediate variations based upon the artist’s skill/knowledge level and intent. See examples 37, 38 and 39 .

Though all of the drawings are very different, they all rely upon some basic

bits of artistic technique. Below is a list of some areas that one must gain

some knowledge in to develop technique.

n Rules of light and shadow – how light

effects basic volumetric shapes

n Basic Linear perspective - 1 and 2D, circle

in perspective, practical application - apparent horizon line

n Additional rules for creating depth

of space, overlap, size placement, atmospheric perspective

n Line quality variation and edge

handling - texture

n Shading technique – application of

tone to create the illusion of 3D form, rendering

n Advanced techniques

n Materials and media

In Appendix B, I list books that are among my

favorites and how I found them to be of value.

The list does not begin to be exhaustive, and I am sure many extremely

cogent and useful volumes exist that I know nothing about. I leave it to the ambitious student to ferret

out works that add to their information.

That being said, I don’t think this volume would be complete, if I did

not touch on each of these areas in the hope that ideas I have formed over the

years might add some unique, or at least thought provoking, ideas to the

drawing debate.

Rules of Light and Shadow

Every book you encounter on the subject of learning to draw

will show you the basic volumetric solids with tone applied to show the effect

of incident light. Because we see this so much, we have a

tendency (Left-brain tendency) to gloss over this as material we already

understand and don’t need to study. Yet

nothing could be further from the truth.

By copying - remember Close Scrutiny? -

good representations of these toned shapes and not all books on the

subject have “good” versions, you are committing to your memory bank vital

information that will help you to improve the look of everything you draw (Now

if you are using a dull, “gnawed by a beaver” 4B pencil on a 2 or 3” drawing I

can’t guarantee the results- use several pre sharpened HB or B pencils for best

results). A solid, fully internalized

understanding of the rules of light is essential if you want to make good

realistic drawings. I think of light in

three different ways.

n A naked bulb is referred to as a

Point source and its rays are radiating on all directions

n The Sun is also a point source but for us the Sun’s rays are considered parallel rays to one another. Why? See example 54 .

n Randomly scattered ambient

light. This is the kind of light you

might think of on a grey overcast day, where cast shadows are very faint or

non-existent.

For practical purposes, although there are differences in the

rendering of highlights and cast shadows on objects, Point source and Sun’s

rays act similarly, and randomly scattered ambient light doesn’t give us much

tonal variation to work with. Examples_55

and 56 show the application of simple shading to more complex objects. Remember, a drawing of an object is an

illusion, an avatar of the actual

object, and as such the illusion is subject to the artistic skills of the

draftsman. One of the things it took me

a while to catch on to back when I was making those “hit by a truck” drawings

of the figure was that if I tried to draw every nuance of shadow on the form

while I was still struggling with the shapes and relationships, I became

hopelessly lost and frustrated, and my figures appeared to have contracted some

sort of horribly disfiguring skin disease before they were hit by the truck. A

lot of this was due to my lack of touch

with the pencil, but mostly it was due to the misapprehension I had that I

should be including every subtle tone in my ½ hour or 20 minute drawing. What happens in practice, or at least it did

for me, finally, was to make up my own light source! So if I was confronted with a confusing or

non existent shadow /shade pattern, I concentrated on getting the form correct,

and when it came to shading I would assume the light was coming from say the

upper right and add shadow to the forms accordingly. This was possible because I had learned the

“Rules of light and Shadow.” See the diagram on p x . Remember, a drawing is an illusion, created

by you. You are not tied to a literal

translation of anything. Rather, you

weave a spell, part real, and part trickery (read here, learned technique), to

make the illusion complete.

When the light source

on a subject is confusing, create your own light source, once you have learned

the rules of light and shadow, of course.

Diagram 57 below shows the effect of parallel ray light

coming from the upper right on several basic volumetric shapes (simple

forms).

We see objects because part of the light, bouncing off of the

object’s surface is reflected to our eye.

The surface tonalities we perceive are a function of the surface

texture (rough, shiny, wet etc.),

object shape and quality of the incident

light. Some artist’s have become very

adept at describing not only surface qualities of objects but complex lighting

conditions as well. As a first step in

developing those more advanced skills you must learn how light hitting basic

three dimensional (3D) shapes behaves.

Basic 3D shapes are the cylinder, the sphere, the rectilinear solid and

the cone. Virtually all complex forms we

see, both natural and manmade can be approximated by one , a combination or a

variation on these simple shapes. It

might even be said that developing your ability to analyze complex shapes in

this way is an essential part of the Blocking

In concept described in The "Seeing" section.

You should know the rules embodied in this diagram backwards

and forwards. Practice drawing the forms

and trying the lighting from different directions. Learn how to draw cylinders, especially the

elliptical ends (see circle in perspective p__). Understand and use reflected or “wrap around”

light which allows you to separate on object from another. See examples 58

and 59 . When making

copies of master drawings, look for ones that pay particular attention to the

subtleties of light and shade used in their execution and learn from them. Robert Beverly Hale was a preeminent American

teacher of anatomy and one of his books, Drawing Lessons of the Great

Masters is a great resource not only

of drawing and rendering tips but also of Master Drawings suitable for copying.

Examples 60

and 61 are a good drawing exercise to practice the

application of light and shade. After you have completed them check your result

against mine in Appendix___ .

Application of tone

I was conflicted about whether to put this section before the

previous one on rules of light and shadow since they are so interrelated. I leave it to you to go back and apply

anything you might pick up here to previous concepts or exercises.

Many books on drawing lay out the basics of tone application

something like this:

n Continuous Tone

n Dots

n Cross hatching

n Scribble

These are among the most used ways of applying tone, but in reality tone can be applied in any way you chose or in any way your powers of invention come up with. Because, tone, no matter how it is applied, is the buildup of media on the ground or paper surface, and being able to modulate or control the lightness or darkness of the applied media (touch) determines the look of the resulting illusion.

Another consideration: in a drawing consisting of both contours and tone, if the contours are convincing (in figure drawing, if you know your anatomical shapes well) the tone application is secondary to the contour shapes see Example 66 .

I occasionally tell students that you can practically throw dog poop (very loose application of tone) at a drawing and it will work if the contours are correct.

I don’t recommend this as an approach, though I have seen some very successful drawings that used a very loose application of media but were structurally sound because of the knowledge of underlying form evident in the work. Larry Rivers, one of the major figures in the post AE* pop art scene of the late 20th century made some exquisite drawings which relied on smear erasures , left out details and “artful” messiness. See Example 67 .

Many of the early

masterworks which still exist were preliminary sketches for large scale

paintings, frescos and alter pieces. The

artists who made these pieces were most often schooled in an apprentice system

and learned to draw anatomy over periods of years. They were very knowledgeable, and their

drawings were often quickly done - the way you might sign your name – and the

incredible facility shown was deeply rooted in a profound understanding of the

human form. So, in many cases, their

application of tone, was just a quick shorthand delineation of the location of

shaded areas. We see this especially in

the loose application of a single pass of hatching marks running across the

form (laterally rather than longitudinally)

see Examples 68 and 69 .

Yet the illusion of solid form is uncanny, and this is why we can derive great

benefit from studying (read “copying” see Chapter 3 ) these works. An incredible book by Philip Rawson called Drawing,

Second Edition, has some very enlightening sections dealing with tone

application and contours. Jeno Barcsay,

in the Anatomy for the Artist I mentioned early on was a master of using

cross hatching and by its careful buildup producing continuous tone. See example 70 . [ add Cvardi]

Paul Calle an illustrator developed an incredible technique for application of tone

using pencils. See Example 71 .

Kathe Kollwitz, a modern 20th century master, made drawings

using broad chunks of a graphite or compressed charcoal stick which is another

variation on the application of tone.

See Example 72 . I have a

book by Saul Steinberg called The Inspector, and it contains some of the

most inventive uses of tone application I have ever encountered. See examples 73 and 74 .

This brings me to an important point that needs restating: knowledge of technique will greatly

enhance your artwork, but if the underlying shapes and relationships are not

correctly seen, then the final image will not be successful. We can make an analogy with contemporary

cinema, Let’s take knowledge of object

structure as “story line,” and applied tone technique as special effects. We have seen that if the story is weak to

begin with, no amount of special effects will improve the final result. Likewise, if we don’t have good knowledge of

the structures we are drawing, then the tone application, no matter how

impeccable or “slick” won’t save the drawing .

See Example 75 .

A couple of additional thoughts:

n Cross Hatching - because it is so prevalent as a technique, it

is worth the effort to gain competence.

I’ll offer some suggestions for those needing a baseline tone